It seemed as if Bobby had been gone for months instead of sixteen days. When she returned home from England where she had attended her only sibling’s funeral following his unexpected death, the excitement of being together kept us awake talking long after our usual bedtime.

Two days after our joyful reunion, on September 27, Bobby waved goodbye as she pedaled off to return a sweater at the Arsenal Mall in Watertown. An hour later, the phone rang. Since the number was unfamiliar, I hesitated before answering. When a woman’s voice asked if I was related to Roberta Wiggins, my heart stopped. For years, long before Bobby lost most of her hearing, I’d had a premonition that Bobby would have an accident while riding her bicycle. I considered asking her to stop biking but knowing the joy and sense of freedom it gave her, I couldn’t myself to do it. Also, I’m a fatalist, believing our end time is predetermined, unable to delay the angel of death.

“Yes! Yes, I’m her husband! What happened?”

“She’s been hit by a large truck…her leg…so much blood. The police, ambulance are coming!”

Frantic, I called the Watertown Police who assured me that someone would call back as soon as they knew where Bobby had been taken. Fifteen long minutes later, they said she was in Beth Israel Hospital Trauma Center. A neighbor drove me over.

I was led into the Waiting Room. One hour passed. Another hour.

“Where is Bobby,” I asked.

“As soon as she is out of the OR, we will come for you.”

On the five o’clock news, there was a short segment about a truck hitting a bicyclist in Watertown. When I saw the size of the vehicle, my heart dropped. How could her slight frame survive such an impact? Two more hours passed. Finally a nurse guided me through long corridors and up an elevator to the E R Trauma Center. The scene was impossible to comprehend. With so many IVs, a breathing machine with a large tube down her throat, I could barely recognize my wife. The young nurse did her best to answer my questions.

Near midnight, a doctor entered. “The miracle here is that she’s alive,” he said. “We’ll need another miracle for her to survive without catching an infection or pneumonia.”

A day later, our long time friend, Diane, came to stay with me. As we walked to Beth Israel each day, we’d tell old stories about Bobby, unable to digest the seriousness of her condition. We sat in silence watching her motionless body, listening to the sound of the breathing machine in the antiseptic glare of fluorescent light, never mentioning the tube sucking blood from some unknown place under the sheets into a canister.

For eight days, Bobby’s severe wounds needed to be changed daily in the OR under anesthesia. I asked the nurse why the breathing tube needed to remain in place. “I want to talk to her.” When the tube was finally removed, Bobby’s vocal cords were traumatized, rendering her unable to eat or drink. She spoke with a whisper but at least we could talk, and when her beautiful blue eyes focused on me, I cried.

Finally, Bobby was moved from the ICU to a private room. The sun shone in the windows. The nurses were so caring, every few days one would braid Bobby’s hair. As her bandages were being changed, I found the courage to take a look. My God, the damage was inconceivable. But hope serged whenever her eyes met mine. I remarked to Diane how Bobby’s demeanor had become almost childlike, innocent. Diane had noticed as well. Andy, Diane’s husband, joined us on our daily visits. The three of us sang devotional songs to Bobby. Her eyes stayed riveted on Andy as he led the song.

Friends came for a short visit. I couldn’t tell if they thought Bobby was doing well or dying. Someone asked how long I stayed each day. ”All day, 7-8 hours,” I said. “What do you do all that time,” they asked? I had to think because the time passed so quickly. I loved being with her, massaging her feet, helping her with simple exercises, and chatting like we’d done for over 50 years. There was nowhere I’d rather be.

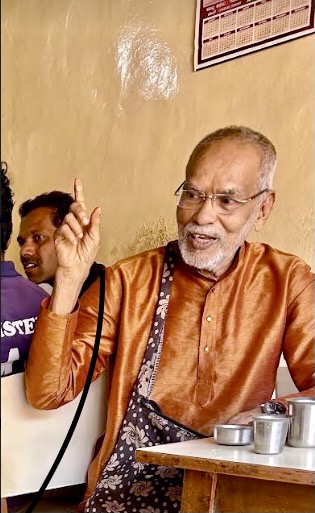

After three weeks, Bobby’s progress slowed. Full of hope, we didn’t seem to notice or didn’t want to notice. But when both Diane and I noticed Bobby peering at her massive wounds with an expression of disbelief, our hope waned. I continued to ask questions about her progress and how they planned to skingraft such a large area. Definitive answers were rare, but a nurse said it was good to ask questions; Bobby needed an advocate. Another week passed as her condition continued to decline, Bobby began to have spiritual visions.Her Guru appeared to her within. I’d heard of Indian followers of the Saint having similar experiences but for Bobby to confirm that our Guru had come to support her was awe inspiring. Diane, Andy and I were so moved by her proclamations that we temporarily forgot the seriousness of Bobby’s broken body.

Despite knowing how dire Bobby’s situation was, the nurses remained positive. They commented how radiant she looked, how bright her eyes were. They were brilliant! Instead of having a touch of green, they were now a vibrant blue. No one had an explanation.

An infection invaded one of the large wounds and found its way into Bobby’s blood steam. Back to the ICU with low, very low blood pressure, kidneys failing and her lungs were filling with fluid. A surgeon told me without dialysis, she couldn’t last.

“And with Dialysis?” I asked.

He looked down, “Her kidneys might rebound.”

“And?”

“Her prognosis is grim.

A meeting was called. Diane sat in. The doctors wanted to persevere. After all the time and energy put in to save Bobby, they didn’t want to quit. I knew that Bobby had no fear of dying; we’d discussed end-of-life issues many times through the years. I asked Diane for her thoughts. She said a few days earlier Bobby had told her how pointless it was to keep her alive.

“No more treatments,” I said. “ let her have some peace before dying.” That’s my decision,”

Bobby was moved to a new room where she drifted in and out of consciousness. Her labored breathing was torturous to listen to, but Diane, who had worked for years in hospice, knew as bad as it sounded, this was normal. “Don’t let them give her morphine, it will cloud her mind. She should be as alert as possible for the transition.”

All night I listening to that death rattle. The next day friends came to stay farewell in silence. How do I say goodbye after 53 years? That night at 9:30, Bobby took her last breath. I sat with her lifeless body trying to grasp what had happened. I couldn’t. But even in my state of shock, the silence in this room was inescapable. Dead silence! Now I understood that expression, without life, there’s only silence. She was pronounced dead at 10:40 pm on Nov.14th. I went home.

Diane and Andy stayed for another two weeks to help me begin the impossible task of adjusting to life without Bobby. Bobby and I were so close, so attached. I felt that half of my heart and soul had just been torn away. At this later date, there will be no recovery for me, just living without intimacy, without the person who knew me inside out and still loved me, without my best friend. And what about all my love for her? It’s turned into grief. ‘Grief is love that has nowhere to go’. Our house is full of her absence, everything reminds me of Bobby.

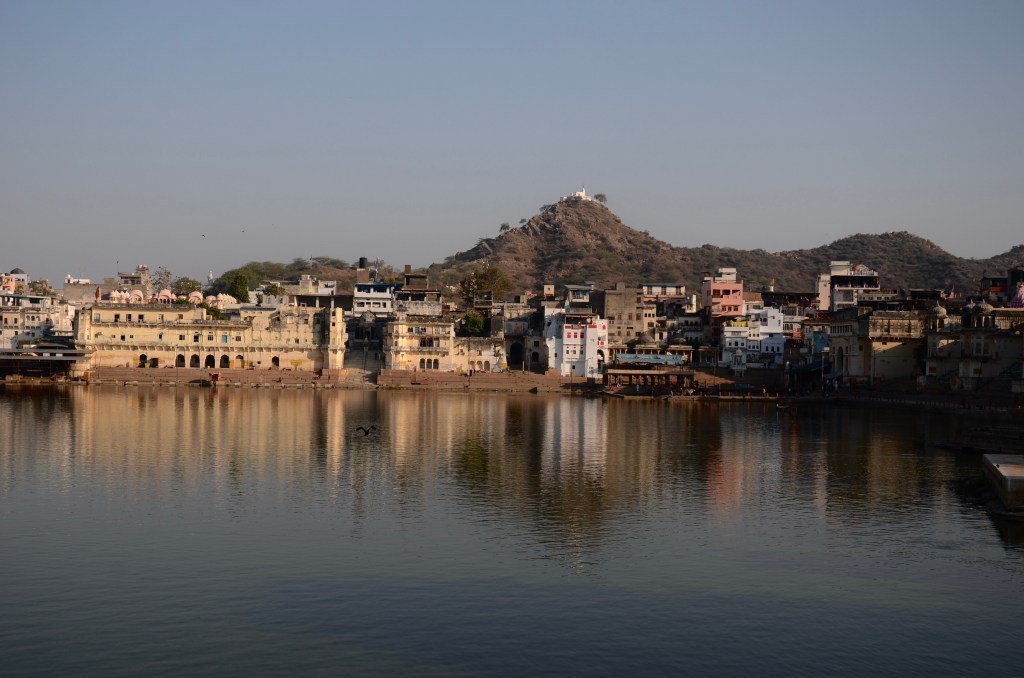

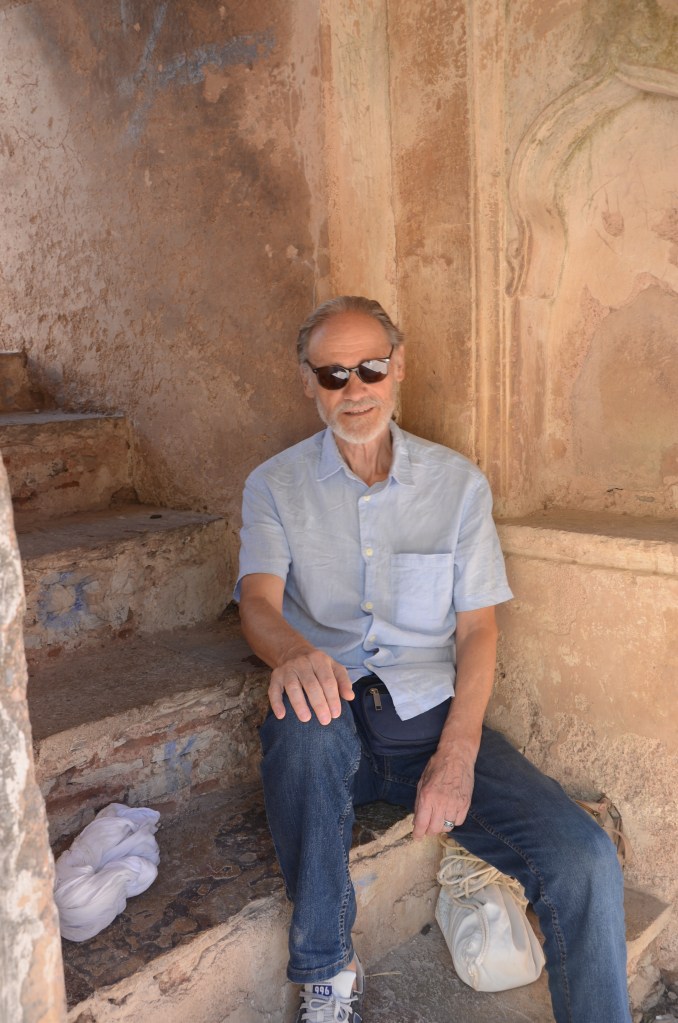

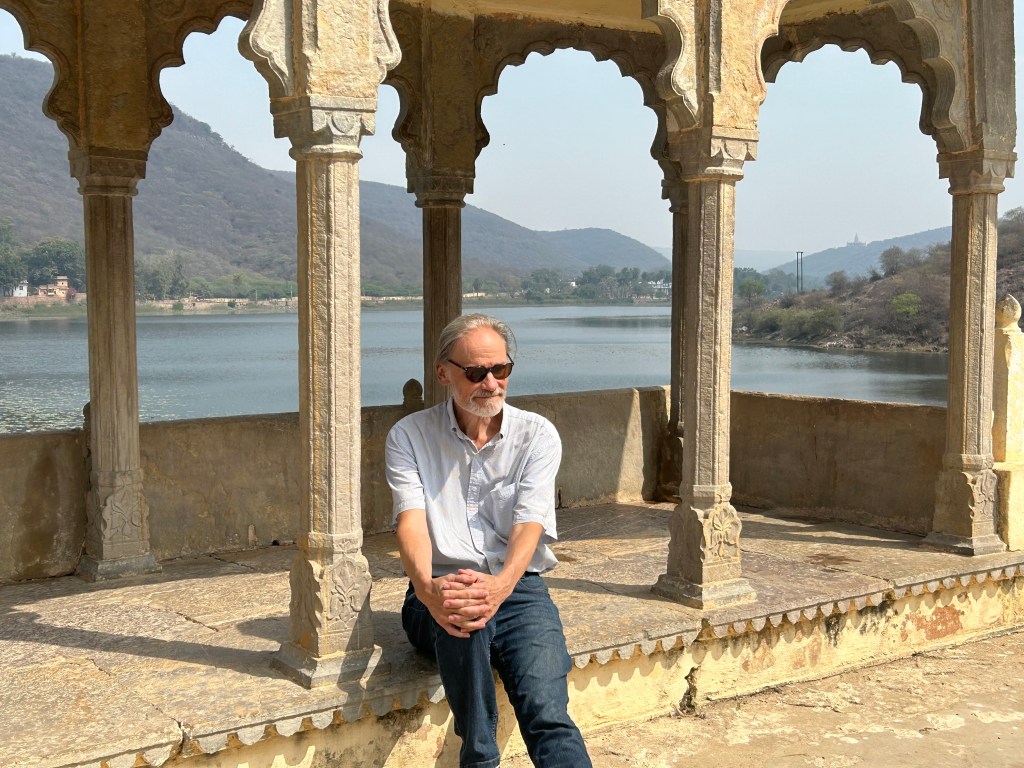

Traveling to India was out of the question this winter. I wonder if I’ll ever return—too many memories.

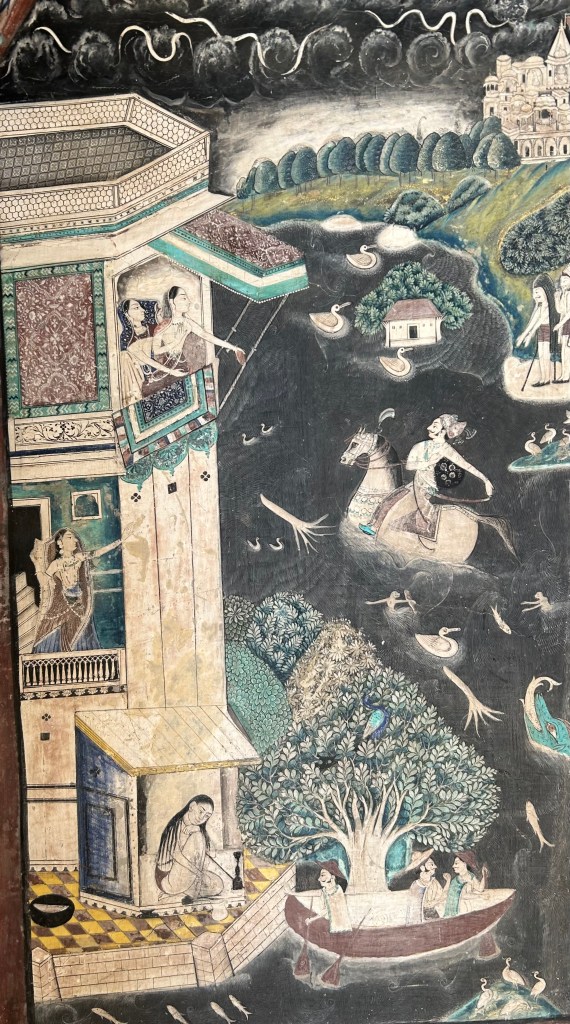

This will be the last entry of A Small Case Across India that Bobby and I took so much pleasure in writing. I hope through the years it captured our love affair with India, its people and culture as well as the love we had for each other. Our marriage was no less than heaven on earth.