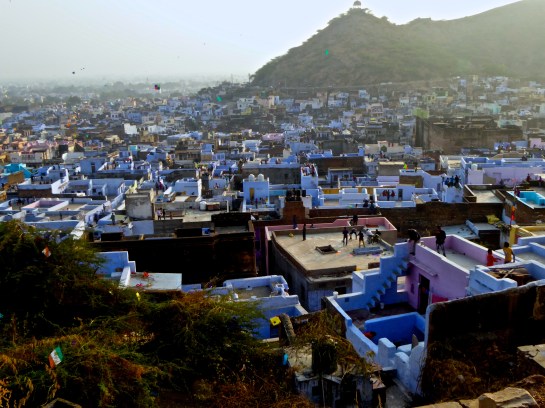

Arriving in Bundi the last day of the kite festival, the sky was littered with paper kites. We all know how the Indians love a festival and this one was no exception. We climbed up the hill at sunset to watch the multi colored kites fluttering high above the blue city.

For a couple of years we’d heard interesting things about Bundi: not only does it have a magnificent Rajput palace, but it also has a pretty lake and the town is scattered with old havelis in various degrees of decay. Never more than a modest market center, according to our guidebook, Bundi has stayed relatively untouched by modern development. We stayed just inside the town walls in one of the havelis converted to a guesthouse, the top floor with magnificent views.

We ate our evening meal on the roof terrace looking toward the palace lit up in an orange glow. At breakfast we sat in an alcove up among tree branches, leaves rustling in the breeze filtering the morning sunshine over the lake.

A colorful bazaar stretched the length of a narrow thoroughfare;

narrower side streets climbed up toward the palace.

It was easy to spend a whole day at the Palace. It is one of the few in Rajasthan whose style has not been influenced by the Moghuls.

Entering through a main gateway adorned with carved elephants, we could wander quite freely among the many rooms and courtyards.

The palace is known for its superb collection of murals. Indeed the paintings were perhaps the best we’ve yet seen in India, all in surprisingly good condition, with limited graffiti or evidence of vandalism. For a little baksheesh, a local with a set of keys was more than happy to unlock the maharani’s dressing room. Every surface of her chamber was covered in finely detailed miniatures, embellished with gold and silver leaf. “Photography not allowed”. The Chittra Sala, the courtesan’s quarters, faced a lush garden. Murals in unusual turquoises, blues and blacks portrayed scenes from the life of the blue faced Krishna.

It was here we met a young Sikh couple from the Punjab. They described to us how they’d met via an online dating service, a common practice among young Indians today. Using filters, they find a partner with similar background, lifestyle and values. In the case of this couple, most critical was finding someone also in the Sikh religion.

Over chai they told us stories of the Rajasthani rulers. Historically, the relationship between the Maharaja and his people was like father and son. They may not have liked each other very much or had anything in common, but were still bound by reciprocal bonds. Taxes supported the extravagant lifestyle of the rulers. On the other side of the coin, when there was a marriage in the village, the raja would send gifts of money; when there was a death, the wood for the funeral pyre would be provided by the palace. Government was embodied in a single person whose actions conformed to tradition. This was possible because of the small size of the Rajas’ kingdoms.

“Size,” the young Sikhs said , “is one of India’s chief problems: it brings distance and impersonality. In the days of the Maharaja you could go to him and tell him your difficulties, and if they were genuine he would do everything he could to help you. But in modern day India, you have to meet with some clerk in a government office for every little thing.”

O ur Sikh friends told us it was Guru Gobind Singh’s birthday – there’s always something to celebrate in India. They invited us to go to the free langar at the Gurudwara. We thanked them, but there was still more of the palace we wanted to see. In the evening, a loud commotion brought us out on the street. We watched a parade of tractors pulling trailers filled with waving Sikhs, ranging from the young to the very old, all on their way to Gurudwara. They’d come in from the country for the festival.

ur Sikh friends told us it was Guru Gobind Singh’s birthday – there’s always something to celebrate in India. They invited us to go to the free langar at the Gurudwara. We thanked them, but there was still more of the palace we wanted to see. In the evening, a loud commotion brought us out on the street. We watched a parade of tractors pulling trailers filled with waving Sikhs, ranging from the young to the very old, all on their way to Gurudwara. They’d come in from the country for the festival.

As we were packing up to leave, we both agreed Bundi was a place we could easily return to.

Customary in arriving at a railway station is to be met by numerous enthusiastic rickshaw drivers, all wanting to give us their best price. We’d been told beforehand that the guesthouse was only a five-minute walk, so we insisted on walking. After five hours on the train, anyway, it felt good to get a little exercise. But we were followed. “Just 10 rupees each, sir.” Walking by choice is not a widely accepted practice in India. One kindly round-faced young man called out, “Free service. Please come.” This can’t be possible. Twice in one day? We got in for the short ride with the promise of hiring him to take us to the Fort the next day.

Customary in arriving at a railway station is to be met by numerous enthusiastic rickshaw drivers, all wanting to give us their best price. We’d been told beforehand that the guesthouse was only a five-minute walk, so we insisted on walking. After five hours on the train, anyway, it felt good to get a little exercise. But we were followed. “Just 10 rupees each, sir.” Walking by choice is not a widely accepted practice in India. One kindly round-faced young man called out, “Free service. Please come.” This can’t be possible. Twice in one day? We got in for the short ride with the promise of hiring him to take us to the Fort the next day.

My father liked to say, “you should never go back.” He had a cynical streak/view of life and believed that you’ll always be disappointed a second time. Just like people, places will let you down. Gerard and I have proved him wrong over and over again. We go back to Varanasi and Goa year after year and are not let down. Rather, it improves as we become more familiar. But certain expectations inevitably form. I’d loved Pushkar the first time we visited last year. It’s a pretty town, sitting beside a lake surrounded by gentle hills and has a spiritual ambience

My father liked to say, “you should never go back.” He had a cynical streak/view of life and believed that you’ll always be disappointed a second time. Just like people, places will let you down. Gerard and I have proved him wrong over and over again. We go back to Varanasi and Goa year after year and are not let down. Rather, it improves as we become more familiar. But certain expectations inevitably form. I’d loved Pushkar the first time we visited last year. It’s a pretty town, sitting beside a lake surrounded by gentle hills and has a spiritual ambience

For eons Indians have dumped their trash wherever they felt like it and it posed little problem – but in the past 50 years with the arrival of plastic it’s now become a serious issue. Trash thrown into the bushes only a couple of meters behind the guesthouse has grown into mounds of plastic and an off-shore breeze picks it up and blows it on to the street and, further, toward the beach. This year we notice construction debris – broken pieces of concrete and tile thrown carelessly along the roadside. It is true that local and state governments have no conception of how to deal with the increasing amount of trash the tourist industry is creating here.

For eons Indians have dumped their trash wherever they felt like it and it posed little problem – but in the past 50 years with the arrival of plastic it’s now become a serious issue. Trash thrown into the bushes only a couple of meters behind the guesthouse has grown into mounds of plastic and an off-shore breeze picks it up and blows it on to the street and, further, toward the beach. This year we notice construction debris – broken pieces of concrete and tile thrown carelessly along the roadside. It is true that local and state governments have no conception of how to deal with the increasing amount of trash the tourist industry is creating here.